Student’s Lynching For Blasphemy Still Haunts Pakistani University

Five years after a mob of students and officials lynched a journalism student on false blasphemy charges at a Pakistani university, fear still permeates the campus as students are taught to avoid tough questions and taboo subjects.

The day is etched in Mukhtar Alam’s memory. On April 13, 2017, he rushed to a journalism lecture at Abdul Wali Khan University, a sprawling campus in the city of Mardan in Pakistan’s northwestern province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

As he entered the classroom, he saw angry classmates surrounding fellow student Abdullah and accusing him of being a heretic because of his friendship with another student, Mashal Khan.

“Abdullah quickly jumped on a chair, recited Kalima (the Muslim declaration of faith), and shouted that he was a proud Muslim,” Alam recalled. “To prove his faith, he cited his parent’s recent trip to Kaaba, the holiest Muslim site. He also mentioned his father’s missionary work, but he was still beaten black and blue.”

Fahim Alam Khan, another journalism student, also witnessed the attack on Abdullah. He says that when he took Abdullah to the hospital, a friend notified him that another mob had stormed the dormitory and attacked Khan.

“When I reached the dorm, I saw Mashal had been badly beaten. They had ripped his clothes off and were hitting him with stones, clay pots, sticks, rods — anything they could get their hands on,” he recalled. “Then they kicked his bloodied, lifeless body down the stairs.”

Fanning The Flames

News of the lynching spread like wildfire as graphic video footage circulated on social media, polarizing Pakistani society over an already divisive subject. Religious zealots justified the attack in the name of punishing blasphemous behavior. Others decried the weaponization of blasphemy laws and called for an investigation, spurring protests across the country and abroad to demand justice for the 23-year-old student.

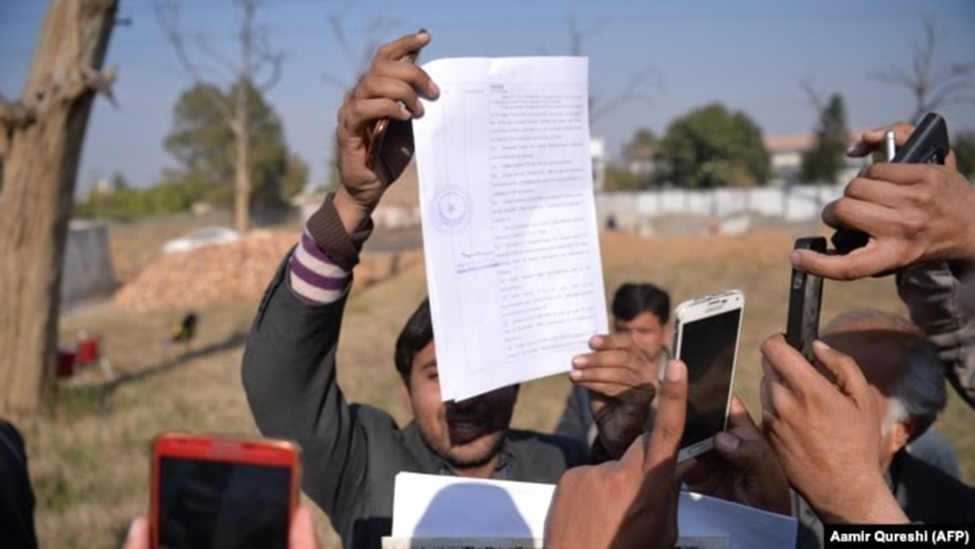

Pakistani authorities appointed a committee that ultimately absolved Khan of any wrongdoing. In its June 2017 report, the Joint Investigation Team said they could find no evidence to back the allegations against him. The team, however, unearthed an elaborate conspiracy targeting Khan for his outspoken views about corruption.

The investigation, ordered by Pakistan’s top court, also recommended the arrest of some 60 students and staff members who were allegedly involved in the mob attack. In 2018, 33 were sentenced to prison while one, Imran Ali, was sentenced to death. His sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment.

But today, discussing Khan’s lynching remains a taboo subject at Abdul Wali Khan University, where more than 11,000 students pursue degrees in humanities, arts, and the social and natural sciences. The fear is so pervasive that scores of students and faculty members refused to talk with Radio Mashaal, citing concerns they would be targeted. Interviews with parents, students, and faculty have suggested that any mention of Khan’s killing — along with any debate, discussion, or freedom of expression over sensitive issues — remains off-limits years after Khan was absolved of blasphemy.

Ahsanullah Zaryan, a poet and former student, says religion cannot be discussed in any form at the university. He says that while studying Pashto literature, he faced a backlash after writing a verse that criticized people who utilized religion for personal gain.

“The pushback forced me to remove the verse from my poem,” he said. “It takes a great deal of courage to discuss any controversy after Khan’s killing. Most of us just keep silent when we sense our views might be labeled as controversial.”

In The Spotlight

On campus, the environment changed radically. The university was closed for a month following Khan’s killing, and there were multiple investigations by national and international press. In response to the spotlight, the administration began imposing restrictions on students and faculty.

Mian Muhammad Salim, the registrar or one of the most senior administration officials, first agreed to talk about life at the university but stopped responding to phone calls and messages after being told the interview would cover the aftermath of Khan’s killing. Several other faculty members refused to talk on the record. One senior official agreed to talk on the condition of anonymity.

He told Radio Mashaal that all political activities were banned and replaced with 20 clubs to engage the youth in “healthy activities.” The administration, he says, appointed some 120 student “proctors” to keep an eye on their classmates and report any violations of the university’s code of conduct.

“They report on whether someone has attempted to enter the campus without a valid ID or if a male student is sitting with a female student,” he said. “Disrespecting teachers or female students and damaging university property are some of the worst violations,” he added, saying the rules are enforced with fines.

He says the increased discipline has boosted the university’s reputation and that it is now receiving recognition for its research. He denies the administration has silenced debates or discussions, pointing out that the institution is part of the larger society in which certain issues are taboo.

The killing of Mashal Khan showed people the invisible red line,” he said. “It taught them what to say about religion and what to keep to themselves.”

Those close to Khan faced a much deeper trauma. Fahim Alam Khan didn’t leave his house for months. He refused to go to the dormitory and only went onto campus for classes, where he met students who’d been absolved of their role in the lynching because of insufficient evidence.

“It killed me to sit next to them,” he said. “I was suspicious of everyone in those days.”

Encouraging Debate

Mukhtar Alam says he was also reluctant to return to the university after the attack. A new journalism professor, Abdul Rauf Yousafzai, helped him overcome his fears enough to be able to graduate.

Yousafzai joined the university the year after Khan’s death. He says he was shocked to see such an environment of fear among the students and began encouraging students to debate noncontroversial issues. The discussion attracted some students who were allegedly involved in Khan’s murder.

“Gradually, we moved on to discussions about difficult issues, and I posed the question of why Mashal Khan was lynched,” he told Radio Mashaal. “I told them they could have achieved the same result by taking him to court.”

Global rights watchdogs and Pakistani activists have called on Islamabad to repeal its blasphemy laws because they are often misused in personal disputes or against non-Muslim minorities.

Yousufzai says that over time his efforts helped some of his students to overcome their fears.

“I used to tell my students that we can break free from fear by talking about what causes it in the first place,” he said.